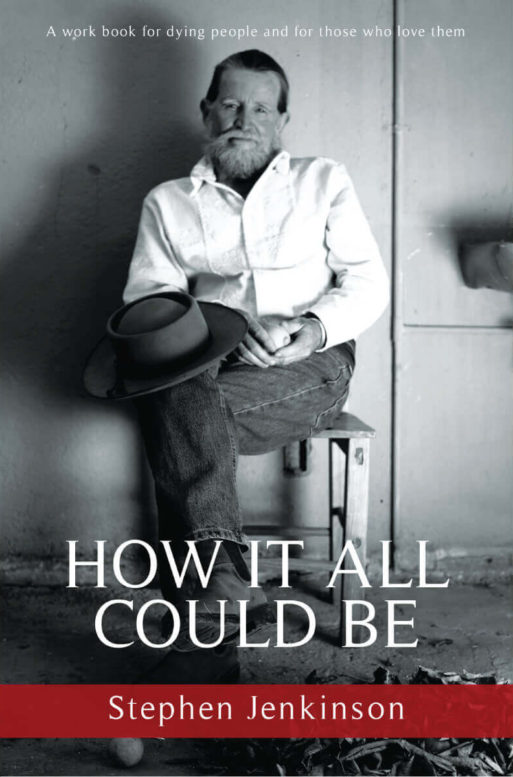

Stephen Jenkinson (MTS, MSW) is an author, teacher, spiritual activist, farmer, subject of the film Griefwalker, and former palliative care professional. His 2009 publication, How It All Could Be: A work book for dying people and for those who love them, offers insightful commentary that strings together a series of deceptively simple questions designed to help regular people think through their feelings, preconceptions and functional relationship with death and grief. He emphatically encourages readers to wonder out loud about these questions – preferably with other people – around a kitchen table, to make this conversation a normal, necessary and life-sustaining thing.

Jenkinson is quick to point out early in the book that he is not offering solutions; he doesn’t offer 12 steps to heal your life, nor a salve to make the pain go away.

Jenkinson is quick to point out early in the book that he is not offering solutions; he doesn’t offer 12 steps to heal your life, nor a salve to make the pain go away. Rather, he unpacks fairly recent ideas about what death is and what grief is for, why we believe these things and how it could all be different. Specifically, he tackles how to open the conversation about death and why this is difficult. He discusses the fear of death and where that fear comes from, accepting the inevitability of death and living as though you will be remembered.

Perhaps the most prevalent point of How It All Could Be is that peace can be made with death by getting to know it, and befriending it:

“Your death was made when you were made, born when you were born, endured what you have endured. It is your adversary – your executioner – only when you grant your death no honor, no place in the order of things, no truth, no seat at the head table in the banquet hall of your life. It is your angel when you begin to see how your death moves and speaks so much like you, when you make sure there is always an empty seat at the head table even when the other guests don’t understand why you’ve done so.”

When we grant our own death a proper place in our lives, we start to consider what our lives will mean to those who we will not live long enough to meet. We must also then consider how we honor our dead (our ancestors) and the space, if any, that they occupy in our personal, collective, private and public lives. And so, it becomes clear that this book was born in a time of rapid mass globalization, written for all those whose ancestry does not originate from the land they call home. Jenkinson asks to us remember who we come from and consider what their lives and deaths mean to us; this is the template from which we can begin to think through what we will mean to others when the physical body is no more. This is not a matter of legacy-leaving, but whether the manner of your life and the way you choose to spend your dying time will help others understand what their own lives and deaths might mean.

These are big ideas, and they tug at a kind of pain that cannot be fixed, solved or ignored. But they give us tools to live courageously, to be honest with ourselves, to understand grief as a symptom of love, and that prayer as the skill of gratitude. Consisting of a mere 37 pages, this is indeed a mighty little lighthouse of a book.

“

How It All Could Be: A Work Book for Dying People and for Those Who Love Them” by Stephen Jenkinson

“

How It All Could Be: A Work Book for Dying People and for Those Who Love Them” by Stephen Jenkinson

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”